JUMP TO:

Bringing Truth to Light

January 9, 2019

James J. Sandman

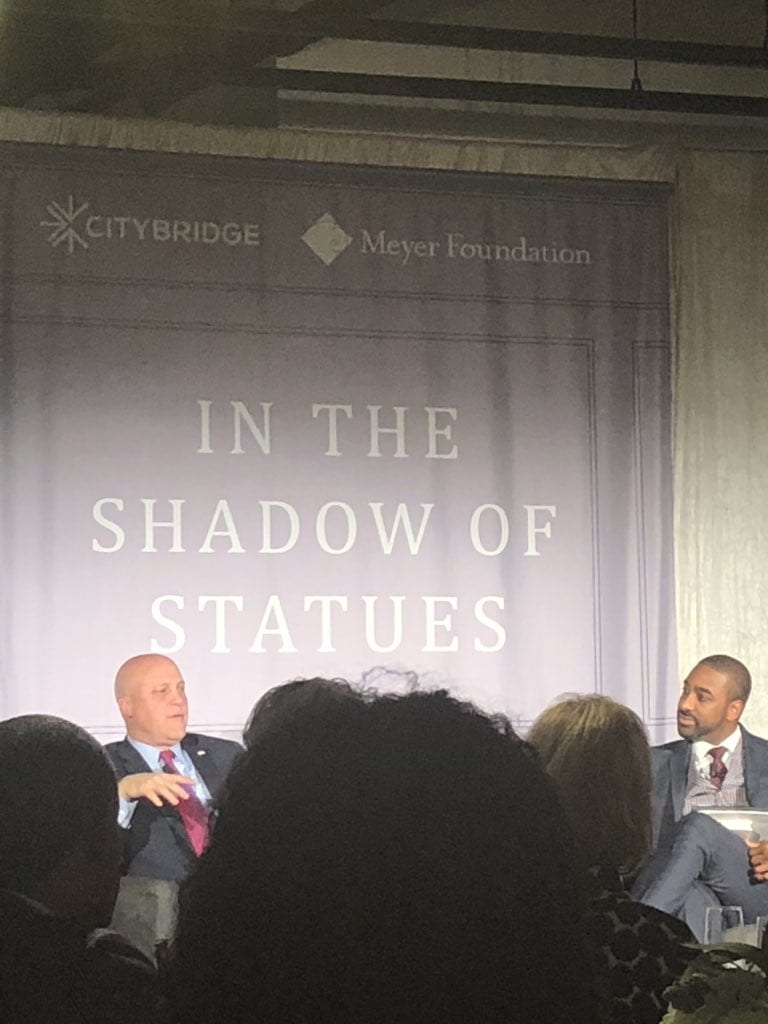

Recently, CityBridge Education and the Meyer Foundation co-hosted a dinner conversation with former Mayor of New Orleans Mitch Landrieu, where he shared insights from his book, “In the Shadow of Statues: A White Southerner Confronts History.” People from the nonprofit, business, and government communities listened as Landrieu recounted the events that led to New Orleans’ removal of four Confederate statues in 2017 and the path toward racial reconciliation that unfolded as a result.

Landrieu’s account, interwoven with his personal narrative as a native of New Orleans and his “transformative awareness” of race and history, was striking. His administration’s attempts to remove the city’s statues honoring Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, and the White League that once sat prominently on display were met with threats of violence. Eventually, private contractors removed the statues, but they were forced to do so in the dark of night and with strong security measures.

I was struck by a number of Mayor Landrieu’s points:

Telling inaccurate, incomplete history has debilitating consequences. I was a history major. I know the importance of knowing all the facts. Every society has a tendency to celebrate the honorable points in its history and to ignore the unpleasant ones. But understanding both the good and the bad is necessary for an accurate picture of where we’ve been. Mayor Landrieu spoke about the effect of his city’s Confederate statues on young African Americans passing by them every day. What message does our society send by celebrating these figures? “They helped distort history […] to distract from the terror tactics that deprived African Americans of fundamental rights from the Reconstruction years through Jim Crow until the civil rights movement and the federal court decisions of the 1960s,” Landrieu writes in his book. No one should ever look at statues of Confederate “heroes” without understanding the horrible, horrible cause – slavery – for which they fought. These are not heroes.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are economic assets. New Orleans’ diversity is a huge asset. Its multicultural traditions, cuisine, and music define the city and contribute mightily to its economy. Much like our own region, New Orleans shows what can happen when people of diverse backgrounds come together, embrace and celebrate their differences, and learn from one another. New Orleans’ resilient recovery from Hurricane Katrina is a lesson in the economic value of diversity.

Dismantling racism is everyone’s work. Mitch Landrieu is a white man. So am I. I experience my privilege every day – from how I’m treated by security guards (they often wave me through with no screening) to how I’m warmly greeted in my grocery store (“Good morning!”). Mitch can talk about race to white people in a way that makes them get it. We need a lot more people like him to speak up. I need to speak up. I need to step up. This is the most important lesson I took from Mitch – that privileged white guys like him, and like me, need to lead and model the battle against the racism that pervades our society.